Training Information

Free Weights vs. Machines: The Debate

The debate on whether machines or free weights are better for building muscle has been around for decades. There was a time not too long ago when machines ruled in the gym world and were ‘the’ way to train.

Then, people realized that while machines are good for training size and strength they neglect key core & stabilization muscles. This paved way to ‘functional’ fitness and people started believing that machines were now bad for you.

So, when it comes to the question of, “Which is better?” It is safe to say that it depends on the person and their ultimate goals. Basically, exercises that may be good for some people may not be for others.

Weight Machines – Pros and Cons

Pros

Easy to learn and use – Most machines have a picture demonstrating its use, which for most machines is pretty self explanatory. This makes them easy to use on their own or with other machines to create your own circuit. If hiring a personal trainer is out of your budget, they are easy to figure out by simply watching the person ahead of you.

Isolate muscle groups more efficiently – Since most of your body is pretty stable on most machines you are able to target the larger muscle groups more efficiently. This is beneficial to those who have a solid foundation and are looking to improve their physique by building bigger muscles. This can be the preferred method for some bodybuilder types.

Allow you to train with heavier weights without assistance – If you are fairly inexperienced with proper technique when using free weights, it may be difficult to add resistance. Some machines will allow you to slap on extra weight without risk of injury. This may also be useful if you are pressing or squatting without a partner or spotter. (Note: proper technique is paramount before you need to worry about adding weight. Train smart.)

May be useful for elderly populations and/or rehab – For someone that has a really low level of fitness and/or is recovering from an injury, machines may be the tool to get their strength up quickly and safely. Since machines isolate it may also be easier to work around certain injuries.

Cons

• Non-functional – Although machines will make you bigger and stronger, they don’t train complete human movement patterns that are necessary to move. Weight machines just don’t translate well into strength and fitness for daily activities, not to mention athletics.

• Neglect smaller stabilizing muscles – Since you are isolating target muscle groups, the important stabilizing muscle groups around the joints take a back seat. If you neglect these smaller muscles for too long, you run the risk of chronic injury and poor posture.

• May cause injury directly and indirectly – Although safer to use with lower levels of skill, it is still possible to use too much weight and enough poor form to cause a serious injury. Overloading the same movement day in and day out is also an easy way to set yourself up for an overuse injury. Form is important and like anything else the danger is in the dose!

• Fill up during peak hours – If you have ever worked out in a commercial gym during peak hours you may have noticed that every machine in the place seems to be filled up. Instead of waiting for that guy that has been on the machine bench press for 20 minutes to get up, head over to the free weight area for some more breathing room.

Who Should Use Weight Machines?

• Beginner – Someone who is very new to the gym and doesn’t know how to properly utilize the free weights just yet. Even though there are pictures on the machines it is worth asking for advice from a personal trainer for proper use.

• Bodybuilders – When size and aesthetics is your main goal there is a lot of efficacy to using machines. For a better more well-rounded physique a combination of both weight machines and free weights is recommended.

• Rehab – Machines may be an easy way to rehab an injury if you don’t have a physical therapist or trainer to work with you. Once you are feeling better it may be better to move to bodyweight exercises and take preventative measures.

Free Weights – Pros and Cons

Pros

• Allow you to train functional movements – This could be a topic on its own, but basically free-weights and bodyweight exercises have greater carryover to what you do in real life such as daily activities as well as athletics.

• You can use full range of motion – You have complete freedom to move around rather than being locked into a specific range of motion or pattern. This allows your body to do what it is naturally built to do, move.

• Place a greater demand on stabilizing muscles – Using free weights will activate more synergistic stabilizing muscles while you are training. Will help to keep your joints healthy and fully operational when done properly.

• More bang for your buck exercises – If you have limited time to train and want to get a lot accomplished with few exercises then free-weights are the way to go. Two favorites are deadlifts and Turkish get-ups. There isn’t a muscle in your body that doesn’t get worked with these two alone!

• Allow for endless variation – With machines you are really limited to what you can do depending on what is available. With free weights, all you need is one dumbbell and you can do hundreds of different exercise variations. Choose one dumbbell and do as many exercises as possible for time. Press, squat lunge, swing and carry are just a few.

• Train anywhere – Learning how to train with free-weights or body weight allows you to literally train anywhere since machines aren’t always available. When going on vacation and travelling by car it is easy to bring a kettlebell, some bands and a TRX to get in some quality training.

• Less expensive – Free weights are the way to go if you don’t have access to a gym since they are much less expensive than machines.

Cons

• Takes some skill to learn proper technique – Free weight exercises have a higher learning curve than machines and you may need someone to show you proper technique. Having a trainer show you or reading a book on weight training may be the way to go. Take your time and try to avoid creating bad habits by copying others that have bad form (e.g. Youtube).

• Greater risk of injury when not done properly – When using bad form it is easy to move a bodypart or joint out of proper alignment and tweak something. This can cause injury so make sure you know what you are doing and use the appropriate weight.

• Need a spotter to lift heavy weight on squat or bench press exercises – Some exercises are difficult to improve on if you don’t have a training partner which may slow down progress. At the very least you can ask a trainer to check your form and maybe give you a quick spot. There is nothing wrong with asking for help.

Who Should Use Free Weights?

• Most people – Pretty much anybody can benefit from using free weights properly to build a strong and lean body using a good program. It is important to build functional strength and muscle to be able to do the things you enjoy and stay active later in life.

• Athletes – To compete at high levels and remain injury-free, athletes’ bodies have to move synergistically and the best way to achieve this is to train the same way. A combination of free weights and bodyweight exercises is the way to go.

• Bodybuilders – The best way to get bigger is to get stronger and the best way to get stronger is through free weights. Once you build up your strength, you can add in some weight machines to isolate and ‘build’ specific muscle groups. The bulk of bodybuilding training comes from free weights but it is ok to add in some isolated machine work too.

• Rehab – Free weights may speed up the rehab process by adding in functional movements to get you moving and feeling better. They may also help you get back to the condition you were in before your injury much faster than using machines would.

Free Weights vs. Machines: Recommendations

For our own strength training programs, we prefer to use mainly free-weight exercises that focus on compound movements and total body strength. Every once in a while, though, we will throw in some bicep curls or use the row machine to change it up a bit.

We hope this list helps you decide which is best for you. At the end of the day, the form of strength training you choose should be based on what your goals are and what makes you feel good. After all, isn’t that what exercise is all about?

Kettle Bells

The kettlebell or girya (Russian: ги́ря) is a cast-iron weight (resembling a cannonball with a handle) used to perform ballistic exercises that combine cardiovascular, strength and flexibility training. It is also the main equipment used in the weight lifting sport of girevoy sport. Russian kettlebells are traditionally measured in weight by pood, which (rounded to metric units) is defined as 16 kilograms (35 lb). Even in American gyms kettlebells will often be referred to in the weight system of poods.

Kettlebell movements

Kettlebell Swing: The kettlebell swing is a basic kettlebell exercise that is used in training programs and gyms for improving the posterior chain muscles. Kettlebell swings are an easy exercise to intensify by using a heavier kettlebell, increasing the repetitions and/or sets, or by doing one-armed kettlebell swings.

Kettlebell anatomy

Unlike traditional dumbbells, the kettlebell's center of mass is extended beyond the hand, similar to Indian clubs or ishi sashi. This facilitates ballistic and swinging movements. Variants of the kettlebell include bags filled with sand, water, or steel shot. The kettlebell allows for swing movements and release moves with added safety and added grip, wrist, arm and core strengthening.

Exercise

By their nature, typical kettlebell exercises build strength and endurance, particularly in the lower back, legs, and shoulders, and increase grip strength. The basic movements, such as the swing, snatch, and the clean and jerk, engage the entire body at once, and in a way that mimics real world activities such as shoveling or farm work.

Unlike the exercises with dumbbells or barbells, kettlebell exercises often involve large numbers of repetitions. Kettlebell exercises are in their nature holistic; therefore they work several muscles simultaneously and may be repeated continuously for several minutes or with short breaks. This combination makes the exercise partially aerobic and more similar to High-intensity interval training rather than to traditional weight lifting. In one study, kettlebell enthusiasts performing a 20 minute snatch workout were measured to burn, on average, 13.6 calories/minute aerobically and 6.6 calories/minute anaerobically during the entire workout - "equivalent to running a 6-minute mile pace".

The movements used in kettlebell exercise can be dangerous to those who have back or shoulder problems, or a weak core. However, if done properly they can also be very beneficial to health. They offer improved mobility, range of motion and increased strength.

Aerobic Exercise

Aerobic exercise (also known as cardio) is physical exercise of relatively low intensity that depends primarily on the aerobic energy-generating process. Aerobic literally means "living in air", and refers to the use of oxygen to adequately meet energy demands during exercise via aerobic metabolism. Generally, light-to-moderate intensity activities that are sufficiently supported by aerobic metabolism can be performed for extended periods of time. The intensity should be between 60 and 85% of maximum heart rate.

When practiced in this way, examples of cardiovascular/aerobic exercise are medium to long distance running/jogging, swimming, cycling, and walking, according to the first extensive research on aerobic exercise, conducted in the 1960s on over 5,000 U.S. Air Force personnel by Dr. Kenneth H. Cooper.

Aerobic versus anaerobic exercise

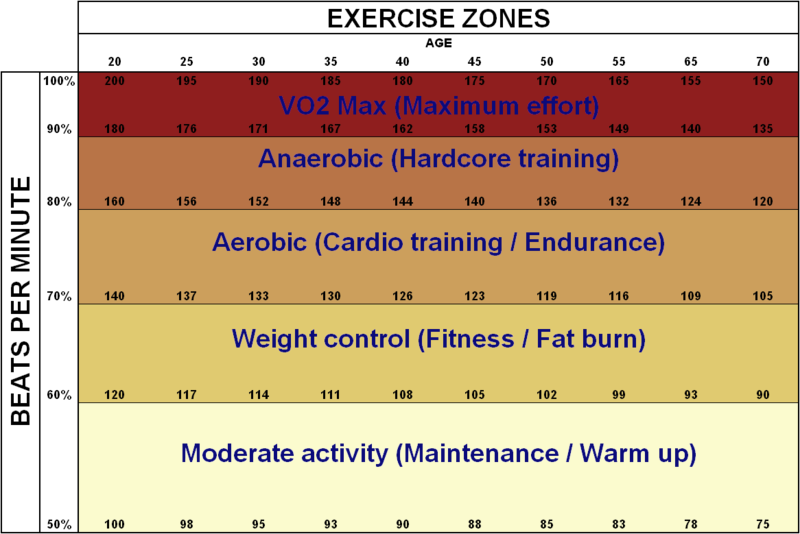

Fox and Haskell formula showing the split between aerobic (light orange) and anaerobic (dark orange) exercise and heart rate.

Aerobic exercise and fitness can be contrasted with anaerobic exercise, of which strength training and short-distance running are the most salient examples. The two types of exercise differ by the duration and intensity of muscular contractions involved, as well as by how energy is generated within the muscle.

New research on the endocrine functions of contracting muscle has shown that both aerobic and anaerobic exercise promote the secretion of myokines, with attendant benefits including growth of new tissue, tissue repair, and various anti-inflammatory functions, which in turn reduce the risk of developing various inflammatory diseases. Myokine secretion in turn is dependent on the amount of muscle contracted, and the duration and intensity of contraction. As such, both types of exercise produce endocrine benefits.

In most conditions, anaerobic exercise is accompanied by aerobic exercises because the less efficient anaerobic metabolism must supplement the aerobic system due to energy demands that exceed the aerobic system's capacity. What is generally called aerobic exercise might be better termed "solely aerobic", because it is designed to be low-intensity enough not to generate lactate via pyruvate fermentation, so that all carbohydrate is aerobically turned into energy.

Initially during increased exertion, muscle glycogen is broken down to produce glucose, which undergoes glycolysis producing pyruvate which then reacts with oxygen (Krebs cycle, Chemiosmosis) to produce carbon dioxide and water and releases energy. If there is a shortage of oxygen (anaerobic exercise, explosive movements), carbohydrate is consumed more rapidly because the pyruvate ferments into lactate. If the intensity of the exercise exceeds the rate with which the cardiovascular system can supply muscles with oxygen, it results in buildup of lactate and quickly makes it impossible to continue the exercise. Unpleasant effects of lactate buildup initially include the burning sensation in the muscles, and may eventually include nausea and even vomiting if the exercise is continued without allowing lactate to clear from the bloodstream.

As glycogen levels in the muscle begin to fall, glucose is released into the bloodstream by the liver, and fat metabolism is increased so that it can fuel the aerobic pathways. Aerobic exercise may be fueled by glycogen reserves, fat reserves, or a combination of both, depending on the intensity. Prolonged moderate-level aerobic exercise at 65% VO2 max (the heart rate of 150 bpm for a 30-year-old human) results in the maximum contribution of fat to the total energy expenditure. At this level, fat may contribute 40% to 60% of total, depending on the duration of the exercise. Vigorous exercise above 75% VO2max (160 bpm) primarily burns glycogen.

Major muscles in a rested, untrained human typically contain enough energy for about 2 hours of vigorous exercise. Exhaustion of glycogen is a major cause of what marathon runners call "hitting the wall". Training, lower intensity levels, and carbohydrate loading may allow postponement of the onset of exhaustion beyond 4 hours.

Aerobic exercise comprises innumerable forms. In general, it is performed at a moderate level of intensity over a relatively long period of time. For example, running a long distance at a moderate pace is an aerobic exercise, but sprinting is not. Playing singles tennis, with near-continuous motion, is generally considered aerobic activity, while golf or two person team tennis, with brief bursts of activity punctuated by more frequent breaks, may not be predominantly aerobic. Some sports are thus inherently "aerobic", while other aerobic exercises, such as fartlek training or aerobic dance classes, are designed specifically to improve aerobic capacity and fitness. It is most common for aerobic exercises to involve the leg muscles, primarily or exclusively. There are some exceptions. For example, rowing to distances of 2,000 m or more is an aerobic sport that exercises several major muscle groups, including those of the legs, abdominals, chest, and arms. Common kettlebell exercises combine aerobic and anaerobic aspects.

Among the recognized benefits of doing regular aerobic exercise are:

Strengthening the muscles involved in respiration, to facilitate the flow of air in and out of the lungs

Strengthening and enlarging the heart muscle, to improve its pumping efficiency and reduce the resting heart rate, known as aerobic conditioning

Improving circulation efficiency and reducing blood pressure

Increasing the total number of red blood cells in the body, facilitating transport of oxygen

Improved mental health, including reducing stress and lowering the incidence of depression, as well as increased cognitive capacity.

Reducing the risk for diabetes.

As a result, aerobic exercise can reduce the risk of death due to cardiovascular problems. In addition, high-impact aerobic activities (such as jogging or using a skipping rope) can stimulate bone growth, as well as reduce the risk of osteoporosis for both men and women.

Pros

In addition to the health benefits of aerobic exercise, there are numerous performance benefits:

Increased storage of energy molecules such as fats and carbohydrates within the muscles, allowing for increased endurance

Neovascularization of the muscle sarcomeres to increase blood flow through the muscles

Increasing speed at which aerobic metabolism is activated within muscles, allowing a greater portion of energy for intense exercise to be generated aerobically

Improving the ability of muscles to use fats during exercise, preserving intramuscular glycogen

Enhancing the speed at which muscles recover from high intensity exercise

Cons

Some downfalls of aerobic exercise include:

Overuse injuries because of repetitive, high-impact exercise such as distance running.

Is not an effective approach to building lean muscle.

Only effective for fat loss when used consistently.

Both the health benefits and the performance benefits, or "training effect", require a minimum duration and frequency of exercise. Most authorities suggest at least twenty minutes performed at least three times per week.

Aerobic capacity

Aerobic capacity describes the functional capacity of the cardiorespiratory system, (the heart, lungs and blood vessels). Aerobic capacity is defined as the maximum amount of oxygen the body can use during a specified period, usually during intense exercise. It is a function both of cardiorespiratory performance and the maximum ability to remove and utilize oxygen from circulating blood. To measure maximal aerobic capacity, an exercise physiologist or physician will perform a VO2 max test, in which a subject will undergo progressively more strenuous exercise on a treadmill, from an easy walk through to exhaustion. The individual is typically connected to a respirometer to measure oxygen consumption, and the speed is increased incrementally over a fixed duration of time. The higher the measured cardiorespiratory endurance level, the more oxygen has been transported to and used by exercising muscles, and the higher the level of intensity at which the individual can exercise. More simply stated, the higher the aerobic capacity, the higher the level of aerobic fitness. The Cooper and multi-stage fitness tests can also be used to assess functional aerobic capacity for particular jobs or activities.

The degree to which aerobic capacity can be improved by exercise varies very widely in the human population: while the average response to training is an approximately 17% increase in VO2max, in any population there are "high responders" who may as much as double their capacity, and "low responders" who will see little or no benefit from training. Studies indicate that approximately 10% of otherwise healthy individuals cannot improve their aerobic capacity with exercise at all. The degree of an individual's responsiveness is highly heritable, suggesting that this trait is genetically determined.